Betting the Farm on Hemp

STORY BY MARGARET HELTZEL | PHOTOs BY MICHAEL SWENSEN

HARRISON COUNTY, KY – A cattle trailer, carefully parked in the shade of a tree line, contains 4,000 wildcards: young hemp plants. Hundreds of thousands of these little green uncertainties will be planted within a 306-mile radius by first-time hemp farmers.

Nick Farmer studies the labels on jugs of molasses-colored minerals. His wife, Ashley, feverishly Googles the ratios of minerals to water needed to make hemp fertilizer, calling out exact measurements as she comes across them. It’s June, the start of the planting season, and Nick pours about-amounts from the $300 jugs into his 500-gallon water tank.

"These are the things we should have figured out last night," she says as she stares into her phone.

Nick Farmer settles on a ratio and, content with the concoction, climbs into his tractor outfitted with his 1960s tobacco setter that he rigged to plant hemp. He drops the tractor into gear and prepares to start his first round of hemp planting, a giant leap for a family that has grown tobacco in Harrison County, Kentucky, for 20 years.

The transition is a daunting one for Farmer and dozens of other farms throughout the country. For decades, even centuries in some cases, tobacco has been king, a cash-rich crop that has sustained farming families for generations. But a shifting industry and climate change are creating lapses in the rhythm of southern life, forcing farmers to try their luck at creating new traditions.

Enter hemp. It's presented as the solution to the dying tobacco industry. It is more profitable, has numerous uses, and is not as physically demanding compared to tobacco. But, hemp is not certain.

The industry is at the pilot stage. Researchers are still developing guidelines for first-time farmers. Farmers look to each other for clues. Only a handful of tobacco converts in Harrison County, Kentucky, have found any level of success since the University of Kentucky began the hemp pilot program in 2014.

Even Jessica Barnes, the Harrison County Agriculture Extension, is learning as she goes. Her 2018 tobacco crop was drowned by unusually heavy rain just before harvest. Months of setting, topping, and hoping were mowed and left to rot in the soggy fields it was raised from.

Many farmers in the county experienced similar losses that left them with their hands tied, forced to move on from the ingrained tobacco tradition to the experimental hemp trend.

Barnes says, “there’s not a set growing standard yet - there’s not a true, one system.” She believes that the trials and errors of farmers across the state will begin to shape the practice before university research is published.

Adding to the uncertainty are the mixed signals coming out of Washington, D.C.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has been slow to provide legal guidance on hemp products. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of cannabidiol, a hemp product commonly known as CBD oil, to treat seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. But the agency has not approved CBD for broader medicinal uses, and warns that other therapeutic uses are not approved as safe, or effective, and cannot be marketed as such.

That’s why Barnes speaks in if’s and could-be’s as she talked about the future of hemp farming. “The FDA is floating around out there and no one knows what they’re going to do,” she says about a possible ban on CBD. “It’s up in the air.”

Half of the battle with hemp is the striking similarities it shares with its taboo cousin, marijuana. The species are alike in smell, look, and growing practices, but industrial hemp has a lower concentration of THC – the chemical that delivers the sought-after euphoria of smoking pot – than the amount of caffeine in a cup of decaf coffee, less than 0.3 percent.

Yet if you drive by the Circle K on Paris Pike, near the heart of Cynthiana, Kentucky, it only takes a light breeze to carry the nostalgic scent into your window. Willie Nelson suddenly comes to mind, just from a small plot of hemp across the street.

Getting that smell to feel more legal won’t be easy.

National Confusion

The Industrial Hemp Farming Act of 2015 amended the Controlled Substances Act to exclude industrial hemp from the forbidden list.

But five years after the legalization of hemp cultivation, information remains scant. The USDA provides incredibly granular data for an extensive variety of crops grown in the U.S. Crop reports for corn and soybeans provide excruciating points of detail - anybody can go on their website and find interactive data visuals for a number of commodity animals and crops.

Yet the page dedicated to industrial hemp is nothing more than a jumbled definition and a hyperlink to the 2018 Farm Bill.

“UK is doing all they can, but they can’t publish anything until they have hard data,” Barnes says of research and data collection. “You get a lot of farmers who do their own thing and they talk - that goes a long way."

One of the only sources of information right now is Vote Hemp, a national nonprofit advocacy organization dedicated to a free market for industrial hemp. With hemp information so scarce, their data is cited by the Congressional Research Service, the USDA and others.

"We did the hard work to contact each state department of ag and collect data," says Eric Steenstra. "We knew how important it was to quantify the market."

What they found was a growing, but apprehensive market of hemp growers. Planted acreage for hemp tripled nationwide from 2017 to 2018 - from 25,713 to 78,176 acres.

That explosion may seem novel, but it actually represents a resurgence.

The History of Hemp

Hemp had a strong run in Kentucky before tobacco and corn overtook the state’s agriculture industry. According to record, the first hemp crop was planted in 1775 near Danville, Kentucky.

Growing conditions in central Kentucky, the Bluegrass region, were ideal for the leafy plant. Hemp fiber was used extensively in the production of everything from textiles to paper to vehicle insulation. It was also used to make rope, specifically the thick coils used on so many of the boats that steamed to battle in World War I.

Harrison County played an outsized role in the cultivation of hemp, cranking out large quantities well into the 20th Century. Back then, Cynthiana’s Rope-walk Street – since renamed to Walnut Street – was dominated by buildings where workers spent their days hand-spinning, weaving and tying hemp ropes.

But hemp had a rough road ahead of it. A paucity of seeds limited the expansion of the industry. Farmers in Harrison County were forced to discontinue hemp cultivation during the Prohibition era. And then came the final straw.

Tobacco made its move, strong and all at once. It gained in popularity after the Civil War, eventually replacing hemp as the state’s main cash crop. It became tradition, the crop that fathers proudly passed down to their sons.

Kentucky farmers set the cadence of their lives to the agricultural rhythm that tobacco composes. Decades passed. A century passed. And suddenly, the song changed.

Hundreds of acres of land that once hosted flourishing crops of tobacco are now little more than swamps. It started in 2011 when a record 66.35 inches of rain fell on the fields. Those downpours haven’t stopped, with the state accumulating an average of 71.98 inches of rain in 2018.

The results have been dire. Kentucky tobacco crops cashed in at $391 million in 2017. By 2018, it plummeted to $301 million, devastating small tobacco farmers across the state.

Hemp’s Return

Jason Marshall was among the first Kentucky farmers to make the switch.

Marshall was born into tobacco farming, inheriting his farm like so many of his neighbors. The crop carried him through much of his adult life. But he made the transition to hemp seven years ago.

That has made Marshall a relative authority on hemp cultivation, the guy that newer farmers call on to troubleshoot problems that arise in their plots.

Sitting at a card table in the back of his tractor service store, Marshall moves a Coke can ashtray, a remnant from that morning’s game of Euchre. Settling into the plastic of an old, schoolhouse chair, Marshall says, “I don’t consider myself to be an educator – maybe a pioneer paving the way for the people who are coming behind us.”

Marshall has been active in the state capital, working with the Kentucky Department of Agriculture and state legislators to fully legalize the cultivation of hemp. He sees the potential for large corporations to support small farmers by buying into local hemp operations. And he joined forces with three other farmers to create the Kentucky Hemp Farmer Association (KHFA), which is focused on improving the viability of the crop and lobbying for state support.

The KHFA has already grown to nearly one hundred members since forming in 2017.

Marshall even retooled his family business to foster the growing industry. The family owned and operated Marshall’s Tractor Service sells parts, offers repair services, and, now, retools tobacco equipment to work for hemp cultivation.

“The reason I got involved in trying to help push the hemp legalization bill is because I stand at that counter and I see people come in one after another and they don't know what they're going to do. Tobacco is going out,” Marshall says, shuffling a deck of cards. “They've got their farms, and their barns are falling down, their fences are falling in, they can’t afford to fix their equipment.

“They don't have tobacco no more.”

Hemp’s Headaches

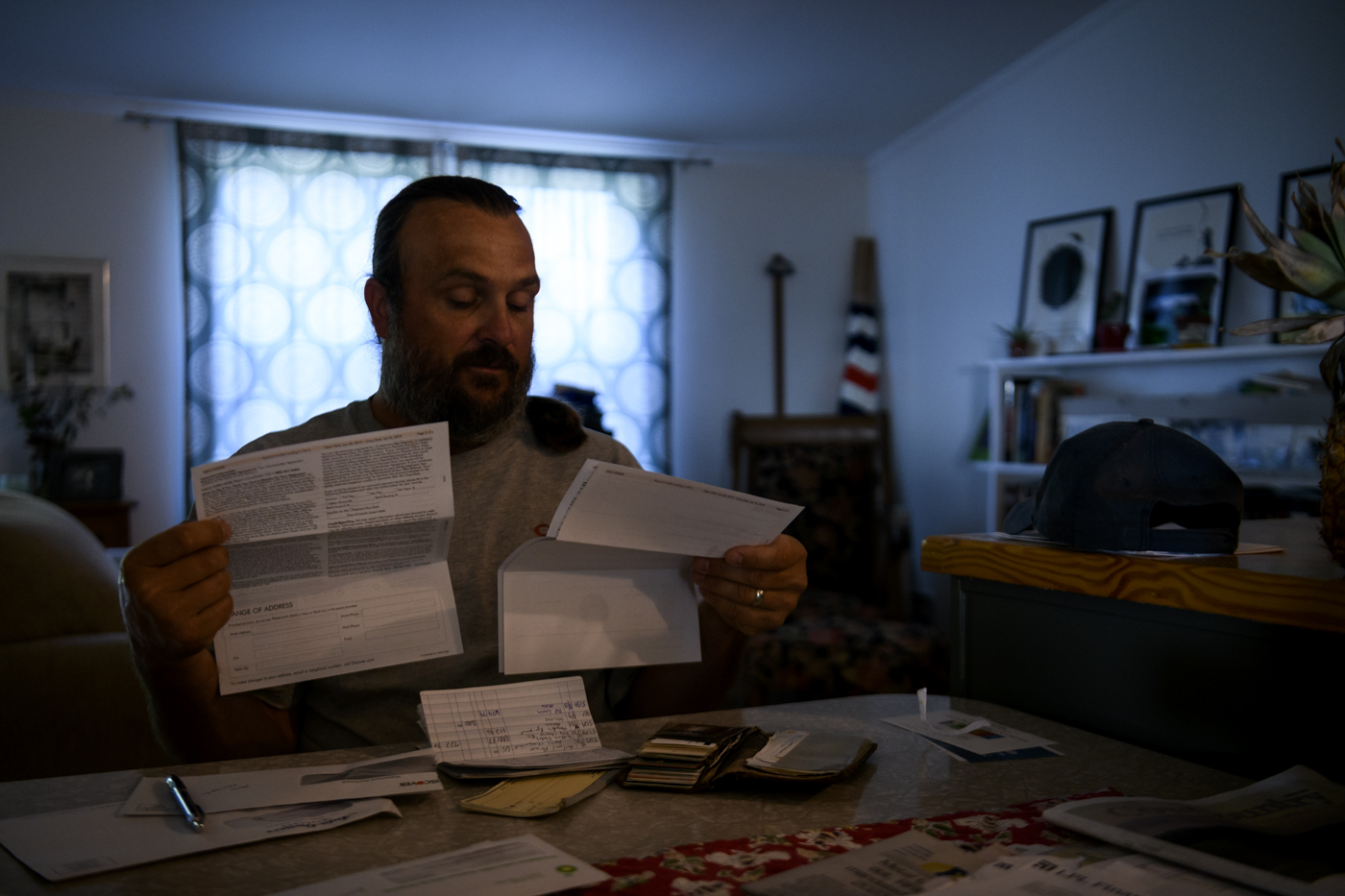

It’s July, and Nick Farmer still has no idea how much hemp he’ll end up with.

Tobacco was a demanding crop. It required constant care and agonizing attention. Over the years, Nick Farmer has touched 80,000 tobacco plants, each one being touched at least six times during a season.

But hemp has its own idiosyncrasies that require a different level of attention, and it all comes down to sex.

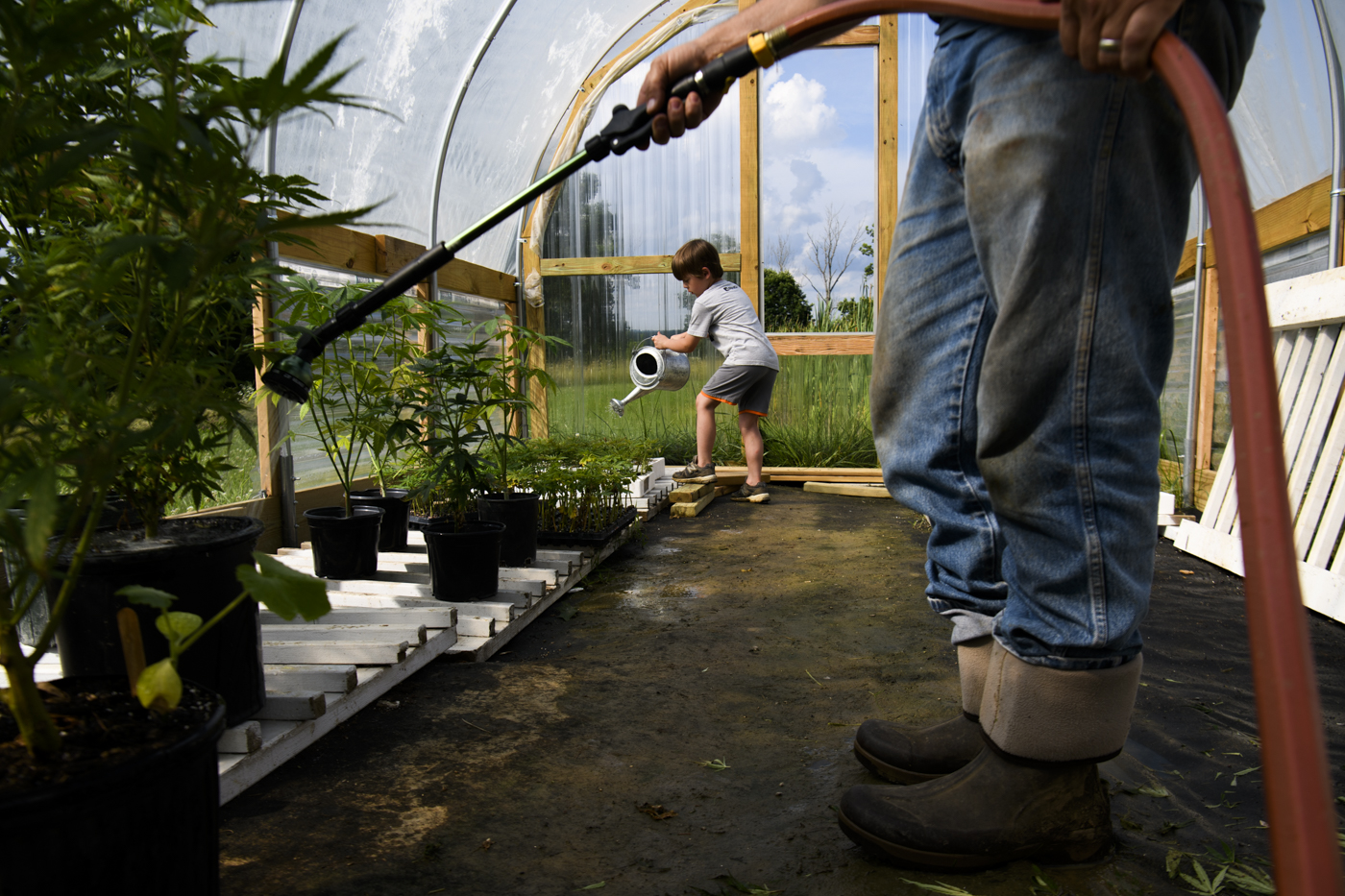

Extracting CBD oil from hemp plants is the most profitable use of the plant, and female plants produce the most oil. Male plants expend so much energy producing pollen that they don’t produce as much oil. That makes female hemp plants the jewels of any hemp field.

That’s why Nick Farmer spent hours in his backyard greenhouse picking out male seedlings and tossing them out. One by one, he’d hold them up and thumb over the plants to find the tell-tale sign of a male: small pollen sacks growing where the leaves meet the stalk.

“The boys have taters,” said his 5-year-old son, Aldo.

Weeding out the males continues throughout the season. Hemp stresses under inconsistent weather conditions, potentially causing female plants to change gender. This transgender issue raises concerns for farmers looking to sell hemp plants with a high-concentration of CBD.

By August, Nick Farmer has pulled nearly 800 males from his patch in effort to deter pollination. “I planted 4,000 and I have 10 left,” Nick Farmer says, facetiously. “That’s the way business goes.”

Still, he trods on. Farmer presses his muddy hands to his forehead as he battles with the fingers of his converted tobacco setter. He can’t afford to lose another $3 plant to a glitch in his calculated plan.

He kneels in the soft soil, dampened by fertilizer, and digs for the hemp plant buried by the setter. He rinses globs of mud off the green gold before hand-planting it where the setter should have dropped it upright, perfectly spaced between its expensive twins.

“I’d be happy if I broke even,” he says.

Going to Market

It’s September, and prices per acre are plummeting.

The influx of first-time hemp farmers has flooded the market, just as they prepare to harvest their first crops. All around, farmers are checking the prices and realizing that sudden drops in the prices may just be the nature of the economic beast.

Tyler Mark, an assistant professor of production economics in the Department of Agricultural Economics at the University of Kentucky, says “it’s a matter of development.”

Dr. Mark spoke to the uncertainty in the hemp industry – a lack of market data, price graphs, risk management, and fixed costs. He believes hemp has legs. The capital investments pouring into the industry show that corporate shareholders see a profit on the horizon, creating an infrastructure that can support high levels of production.

But the production of hemp appears to be far ahead of the current processing capacity in the industry. Existing processors just can’t get through the amount of hemp that farmers have cultivated.

Farmer says the larger processors are just ignoring small farmers like him or telling them to “leave it on the field.”

“The Phil Mor of hemp, GenCanna, is not doing anything with it right now,” Farmer says, comparing Phillip Morris’ empire of Marlboro cigarettes to a top agricultural hemp processor in Kentucky. “They have about $100 million in contracts to pay out to farmers in Kentucky, and they’re not answering calls.”

Jessica Barnes, another farmer near Cynthiana whose growing her own hemp, says that’s led to a staggering level of volatility that is making it impossible for her to know what’s coming.

“We’ve heard anywhere from $5-6,000 an acre to $40-45,000 an acre,” she says. “I still don’t understand the price range. No other commodity has that wide of a range.”

Marshall, the hemp veteran in Cynthiana, likened the chaos to a hurricane.

“It’s like the Wild, Wild West when it comes to getting paid,” he says. “We’ve seen some prices in the past three years that we’ll never see again because they’ll be more and more of it grown. We hope it’ll level off.”

MARGARET HELTZEL

I am a writer - a statement that seems less true as of late. I have spent more of the past six months farm-hopping than I have spent in my usual nook banging away on a rackety keyboard.

Having recently graduated from Ohio University with a degree in journalism, I applied to Boyd’s Station’s Mary Withers Rural Writing Fellowship for the opportunity to contribute to a living archive for a community that is otherwise undocumented.

Boyd’s Station picked me up and dropped me into a cow pasture alongside train tracks and corn fields, and, suddenly, my world opened like the blossoms of the redbud trees lining route 1054.

In addition to writing essays and creative shorts for the archive, it was a chance to dine with regulars in a restaurant that has been hosting a community since 1894, to hear the hard tales of farm foreclosures from the great-great-grandson of the man who first broke the soil, and to feel the rumble of the passing night train as I watch its yellow headlights cut the blue-back sky.

Of all that I gained from my experiences with Boyd’s Station and Harrison County, the most important is the notion that I can make a life in both writing and farm-hopping.

Margaret Heltzel | Ohio University Mary Withers Rural Writing Fellow, 2019

Margaret Heltzel Resume

MICHAEL SWENSEN

Something as simple as a two-finger wave from the dashboard of a passing stranger to flying in an airplane 300 feet above a landscape that I hold close to my heart, Boyd’s Station has taught me how to look for the poetry within rural America. It was the people of Harrison County that taught me how to practice kindness and to wear a callus as a badge of honor.

It was through these gestures that inspired me to return to my family’s 100-acre homestead in Western Pennsylvania (the oldest family owned-farm in Butler County, established in 1792) and cultivate the land as well as create a living archive of my own community. The truth of the matter is that community journalism has never been more important than now. As well as holding tightly to family roots/traditions, I am interested in documenting the massive diaspora that is occurring across the country in these rural areas. Without the encouragement and backing of Boyd’s Station, I am not sure I would have realized this.

While spending time in Boyd I had the opportunity to slow down my photography and take time to become a part of the community. Apart from many internships across the country where assignment work is typically twenty minutes here and twenty minutes there; one is never really given the chance to interact with folks to formulate long lasting relationships. The grant encouraged me to pay homage to the craft. I began by solely focusing on light and color rather than moment and story. I wanted to convey a feeling of the place I was photographing, because that is how I can derive the most meaning out of the work. I wanted to break myself down and rebuild my skills based off of those two variables. It was then that I was able to see the true magic of Harrison County, a deep connection to the land.

Michael Swensen | Ohio University Ed Reinke Grant for Visual Storytelling, 2018

Michael Swensen Website

Betting the Farm on Hemp Image Gallery